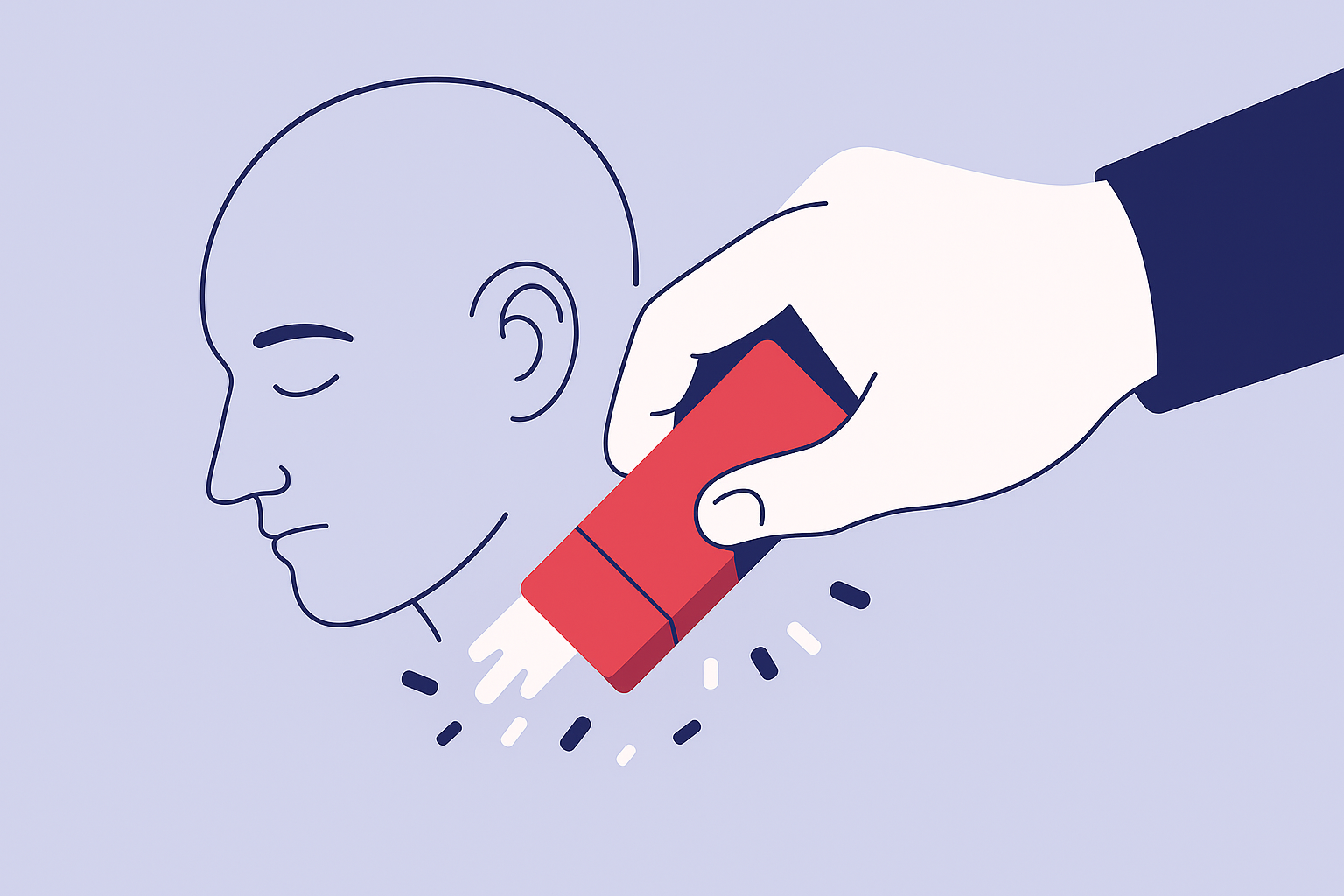

Right to Be Forgotten Online: How to Protect Your Digital Identity

The internet has become a permanent record of our lives. From childhood photos to decades-old news reports, personal data often lingers online long after it serves any purpose. While this digital memory has benefits for transparency and accountability, it also creates challenges for privacy and reputation.

This tension gave rise to the Right to Be Forgotten (RTBF), a legal principle that allows individuals to request the deletion or de-indexing of personal data from search engines and online platforms. Enshrined in Article 17 of the GDPR, it represents a groundbreaking shift in how societies balance freedom of expression and privacy in the digital era.

1. What Is the Right to Be Forgotten?

At its core, the Right to Be Forgotten empowers individuals to ask organizations to delete personal data when:

- The data is no longer necessary for its original purpose.

- Consent for processing has been withdrawn.

- The data is being processed unlawfully.

- The data has become outdated, irrelevant, or harmful.

It is not an unconditional right courts and regulators must weigh privacy interests against the public’s right to access information.

Key Point: The RTBF does not erase content from the internet entirely. Instead, it typically involves de-indexing removing specific links from search engine results under a person’s name.

2. The Landmark Case: Google Spain v. AEPD (2014)

The RTBF gained global attention through the Google Spain v. AEPD & Mario Costeja González case.

- Background: In 1998, a Spanish newspaper published an auction notice about Costeja’s repossessed home due to social security debts. Years later, he argued the outdated information harmed his reputation, even though his debts were long settled.

- Ruling: In 2014, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that individuals have the right to request removal of links to personal data that is “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant.”

This landmark decision forced Google and other search engines to implement processes for handling removal requests, setting the foundation for today’s digital erasure rights.

3. The GDPR and Article 17: Right to Erasure

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), implemented in 2018, codified the RTBF into Article 17 (Right to Erasure).

Key provisions:

- Scope: Applies to all organizations processing EU citizens’ data, regardless of where the company is based.

- Process: Individuals can file requests directly with data controllers (websites, search engines, companies).

- Timeline: Organizations must respond within one month, either complying or providing justification for refusal.

Importantly, GDPR also recognizes exceptions, such as:

- Freedom of expression and information.

- Public interest in health or scientific research.

- Legal obligations requiring data retention.

4. Global Adoption of the RTBF

While Europe leads in codifying this right, other jurisdictions are gradually exploring similar frameworks:

- Argentina & Brazil: Courts have granted individuals the ability to request de-indexing of search results.

- Japan: The Supreme Court has allowed removal requests when outdated information causes significant harm.

- India: High courts have debated cases involving privacy and outdated online content, though no unified law exists yet.

- United States: The First Amendment (free speech) makes an EU-style RTBF unlikely at the federal level, though California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) offers limited rights to deletion.

Observation: The RTBF is shaping into a global privacy standard, though its scope and enforcement vary significantly.

5. Statistics: How Often Is the RTBF Used?

According to Google’s Transparency Report (2024 data):

- Since 2014, Google has received over 5 million removal requests covering nearly 10 million URLs.

- Roughly 43% of requests result in de-indexing.

- Requests most often involve:

- Personal information (addresses, phone numbers, ID numbers).

- Negative press or outdated legal records.

- Sensitive photos and videos.

These numbers highlight both the demand for digital erasure and the complexity of balancing privacy with public interest.

6. How to Exercise the Right to Be Forgotten

If you’re in the EU or another jurisdiction recognizing RTBF, here’s how you can file a request:

Step 1: Identify the Content

Search your name online and list the links that harm your reputation or expose sensitive data.

Step 2: Submit a Request

- Google RTBF Form: Google Removal Request

- Other search engines (Bing, Yahoo) have similar forms.

Step 3: Provide Evidence

Explain why the data is outdated, irrelevant, or unlawful. Supporting documents (e.g., ID, court papers) may be required.

Step 4: Follow Up

If your request is denied, you can escalate it to your national Data Protection Authority (DPA).

7. Limitations and Controversies

While empowering, the RTBF is not without challenges:

- Censorship Concerns: Critics argue it risks erasing history or restricting access to legitimate information.

- Cross-Border Issues: The CJEU ruled in 2019 that Google is not required to remove links globally—only within the EU.

- Public Figures: Politicians, celebrities, and business leaders often face stricter scrutiny; removal is rarely granted if the information serves public interest.

Case Example: In France, former politicians attempted to remove corruption-related articles under RTBF, but courts rejected the requests due to public accountability.

8. Beyond Legal Rights: Practical Reputation Management

Even outside the EU, individuals can take proactive steps to protect their digital footprint:

- Regularly audit your online presence.

- Use privacy settings on social media to limit exposure.

- Request direct takedowns from website owners or hosting providers.

- Hire online reputation management (ORM) firms when content is damaging but not legally removable.

9. Ethical Implications: Privacy vs. Free Speech

The RTBF highlights a fundamental ethical tension:

- Privacy advocates argue individuals deserve control over their personal information, especially when it is outdated or harmful.

- Free speech defenders warn that erasure could suppress journalism, academic research, or public debate.

The future of the RTBF will likely involve nuanced case-by-case balancing of these two fundamental rights.

Conclusion: Taking Back Control of Your Digital Identity

The Right to Be Forgotten is more than a legal tool—it’s a recognition of human dignity in the digital age. While it doesn’t wipe the internet clean, it provides a powerful mechanism to regain control over personal information.

For more details on how to protect your digital rights, see the Electronic Frontier Foundation

As more countries consider adopting similar frameworks, the principle of digital redemption—the ability to move past outdated mistakes—may become a cornerstone of global privacy law.

In an era where data is currency, the RTBF reminds us that individuals are not powerless. With the right tools and knowledge, we can shape how the internet remembers us.

Related Reads on RightsDecoded

- [Why Your Digital Privacy Matters]

- [Data Brokers: The Hidden Industry That Sells Your Information]

- [Navigating Social Media & Privacy]